X-ray physics notes curriculum

Fundamentals of radiation

The X-ray machine

Production of X-rays

Interaction of radiation with matter

X-ray detection and image formation

Image quality

Radiation safety in X-ray imaging (current module)

Fluoroscopy

Mammography

Much of this article will be repetition from module 1 (“key definitions and units of X-ray physics”) but now we have more context, so I think it’s worth revisiting. Feel free to skip if you feel confident with these terms!

To manage and compare radiation exposure safely, several dose quantities are defined.

Each describes a different aspect of radiation interaction with matter, from physical energy absorption to biological risk.

Understanding how these relate is essential for both dose monitoring and radiation protection.

Overview of Dose Quantities

| Quantity | Symbol / Unit | Represents | Used For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbed dose | D (gray, Gy) | Energy absorbed per unit mass | Physical energy deposition |

| Equivalent dose | H (sievert, Sv) | Absorbed dose adjusted for radiation type | Biological effect by radiation type |

| Effective dose | E (sievert, Sv) | Equivalent dose adjusted for tissue sensitivity | Overall risk to whole body |

Absorbed dose (D)

Definition: the mean energy imparted by ionising radiation to matter per unit mass.

D = E / m

Where:

- E = energy deposited (joules),

- m = mass of tissue (kg).

SI unit: Gray (Gy) = 1 joule per kilogram

In basic terms, the absorbed dose attempts to quanitfy the amount of energy being deposited into tissue by ionising radiation. In practice there is a major problem. We can’t directly measure this dose. We have to estimate!

These estimates are created using measured exposure or kerma values. Essentially we measure ionisation and model energy absorption.

Absorbed dose is a derived quantity.

You cannot put a dosimeter into a patient’s organs while imaging them. So all clinical dose estimates are based on indirect measurements and computational modelling.

The reason I’m stressing this point is to highlight that dose estimates for individual patients are extremely difficult to calculate accurately. That is why, as you’ll see now, when trying to define risk we have to talk about risk at a population level and use caution when trying to convey individual risk.

Equivalent dose (HT)

Equivalent dose adjusts the absorbed dose by accounting for the type of radiation depositing energy into tissue. Not all types of radiation are equally damaging biologically. For example, for the same absorbed dose, alpha particles cause more biological harm than X-rays.

To account for the differences in damage (and ultimately risk from ionising radiation) a weighting factor specific to each radiation type is used. The formula is as follows:

HT = DT x wR

Where DT is the absorbed dose, and wR is the radiation weighting factor.

SI unit: Sievert (Sv) (still joules per kilogram because wR is unitless and dimensionless)

A useful tip: whenever the unit Sv is used we are estimating biological risk. Gray is strictly energy deposition without quatifying risk.

Weighting factors (ICRP):

| Radiation Type | Weighting Factor (wR) |

|---|---|

| X-rays, gamma rays, beta particles | 1 |

| Neutrons | 5–20 (energy-dependent) |

| Alpha particles | 20 |

Key point: For diagnostic radiology, absorbed dose (Gy) and equivalent dose (Sv) are numerically the same, because wR = 1. But one estimates risk and the other doesn’t!

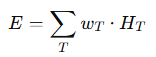

Effective dose (E)

Effective dose accounts for the fact that different organs and tissues have different sensitivities to radiation and ultimately tissue specific risk of stochastic effects.

Tissues are assigned a weighting factor based on their relative propensity to develop cancer after being exposed to radiation. These weighting factors are based on data from atomic bomb survivors and medical exposures. Each organ is assigned a weighting factor and all body organ weighting factors add up to 1. Therefore, the weighting factor adjusts for relative risk based on the organ exposed.

| Tissue / Organ | Weighting Factor (wT) |

|---|---|

| Gonads | 0.08 |

| Bone marrow (red) | 0.12 |

| Colon, lung, stomach, breast | 0.12 |

| Thyroid, bladder, liver, oesophagus | 0.04 |

| Skin, bone surface, brain, salivary glands | 0.01 |

| Remainder tissues | 0.12 total |

Interpretation:

If 10 mGy is delivered to the lungs (wT = 0.12):

E = 10 mGy × 0.12 = 1.2 mSv

Effective dose is calculated by multiplying the equivalent dose by the tissue weighting factor for each organ and adding the values together to get a total risk value.

This can be confusing, so let’s go through a quick example.

Suppose a patient undergoes a CT chest. From dosimetry data and modelling, the following absorbed doses (DT) to different organs are estimated:

| Tissue/Organ | Absorbed Dose DT (mGy) | Radiation weighting factor wR | Tissue weighting factor wT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs | 15 mGy | 1 (X-rays) | 0.12 |

| Breast | 10 mGy | 1 | 0.12 |

| Bone marrow | 5 mGy | 1 | 0.12 |

| Thyroid | 2 mGy | 1 | 0.04 |

| Skin | 3 mGy | 1 | 0.01 |

Step 1: Calculate equivalent dose for each tissue.

Because we are using X-rays the absorbed dose values = equivalent dose but now the unit is Sv. So this step is easy.

Step 2: Weight these equivalent dose values by tissue sensitivity = effective dose.

- Lungs: 0.12 × 15 = 1.8 mSv

- Breast: 0.12 × 10 = 1.2 mSv

- Bone marrow: 0.12 × 5 = 0.6 mSv

- Thyroid: 0.04 × 2 = 0.08 mSv

- Skin: 0.01× 3 = 0.03 mSv

Step 3: Add all the values up!

E = 1.8 + 1.2 + 0.6 + 0.08 + 0.03 = 3.71 mSv

So, the effective dose from this CT chest = ~3.7 mSv.

- This effective dose represents the average stochastic risk of this exam, distributed over all the patient’s tissues.

- For comparison:

- Chest X-ray ≈ 0.02 mSv.

- Natural background radiation per year ≈ 2–3 mSv.

- Thus, this CT chest ≈ equivalent to ~1–1.5 years of background exposure.

Important caveat: Effective dose is an estimate for a reference patient population, not the actual risk for an individual patient.

As mentioned, in practice, measuring absorbed dose is impractical. We can measure dose directly either at the skin surface or as the x-ray beam exits the tube.

To represent these doses we use two metrics:

1. Entrance Surface Dose (ESD)

- Definition: Radiation dose at the patient’s skin surface, including backscatter.

- Measured using: Thermoluminescent dosimeters (TLDs) or ionisation chambers.

- Typical ranges:

- Chest X-ray: 0.1–0.2 mGy

- Abdomen: 3–6 mGy

- Lumbar spine: 5–10 mGy

2. Dose–Area Product (DAP)

DAP = D × A

Where:

- D = absorbed dose (Gy),

- A = irradiated area (cm²).

Unit: Gy·cm². - Measured using a transmission ionisation chamber near the X-ray tube collimator.

- Independent of distance (represents total energy delivered to patient).

- Correlates well with stochastic risk and effective dose.

Relationship Between DAP and Effective Dose

Effective dose can be estimated from DAP using region-specific conversion coefficients (k):

E = k × DAP

Conversion coefficients (k) vary per body region.

Key Takeaways and Exam Tips:

- Absorbed dose (Gy): physical energy absorbed per mass.

- Equivalent dose (Sv): adjusts for radiation type (wR).

- Effective dose (Sv): adjusts for tissue weighting (wT).

- In X-ray imaging, wR = 1

- DAP reflects total energy imparted and correlates with stochastic risk.

- Effective dose (mSv) allows comparison between modalities and estimation of risk on a population level.

- Common exam question: “Define absorbed dose, equivalent dose, and effective dose, and explain how they relate to DAP.”

Up Next

Next, we’ll move on to Biological Effects of Radiation, providing a concise but comprehensive explanation of the mechanisms of radiation damage, dose–response relationships, and key examples of tissue and stochastic effects relevant to diagnostic radiology.