X-ray physics notes curriculum

Fundamentals of radiation (current module)

The X-ray machine

Production of X-rays

Interaction of radiation with matter

X-ray detection and image formation

Image quality

Radiation safety in X-ray imaging

Fluoroscopy

Mammography

In radiology, precision in describing radiation is essential. Different quantities are used depending on whether we are describing the radiation itself, the interaction with matter, the biological effect, or the radioactive source. These distinctions are not just academic: in exams (and in clinical practice), mixing up these terms is a common pitfall.

Here are some definitions of basic terms, and their associated units, used throughout this course:

Energy (eV):

The unit of energy commonly used in radiation physics is the electronvolt (eV).

Definition: 1 eV = the energy gained by a single electron when accelerated through a potential difference of 1 volt.

1 eV = 1.602×10-19 joules

Diagnostic X-rays are in the kiloelectronvolt (keV) range: 20–150 keV.

Exposure (X)

Definition: Exposure is a measure of the ability of a photon beam (X-rays or gamma rays) to ionise air. It quantifies the amount of charge (ions) produced per unit mass of air.

X = Q / m

Where. Q = charge (Coulomb)), and m = mass of air (kg)

Importantly, we talk about exposure in radiology only in the context of X-ray interaction with air. Exposure can be measured in an ionisation chamber. It is useful for calibrating or comparing the output of X-ray machines. Exposure does not define energy deposition in tissue. This is because we can’t measure energy (or more specifically charge) released in tissue.

Units: C/kg (Coulomb per kilogram)

Old units: Roentgen (R) = 2.58 x 10-4 C/kg

Absorbed dose (D)

Definition: the mean energy imparted by ionising radiation to matter per unit mass.

SI unit: Gray (Gy) = 1 joule per kilogram

In basic terms, the absorbed dose attempts to quanitfy the amount of energy being deposited into tissue by ionising radiation. In practice there is a major problem. We can’t directly measure this dose. We have to estimate!

These estimates are created using measured exposure or kerma values. Essentially we measure ionisation and model energy absorption.

Absorbed dose is a derived quantity.

You cannot put a dosimeter into a patient’s organs while imaging them. So all clinical dose estimates are based on indirect measurements and computational modelling.

The reason I’m stressing this point is to highlight that dose estimates for individual patients are extremely difficult to calculate accurately. That is why, as you’ll see now, when trying to define risk we have to talk about risk at a population level and use caution when trying to convey individual risk.

Equivalent dose (HT)

Equivalent dose adjusts the absorbed dose by accounting for the type of radiation depositing energy into tissue. Not all types of radiation are equally damaging biologically. For example, for the same absorbed dose, alpha particles cause more biological harm than X-rays.

To account for the differences in damage (and ultimately risk from ionising radiation) a weighting factor specific to each radiation type is used. The formula is as follows:

HT = DT x wR

Where DT is the absorbed dose, and wR is the radiation weighting factor.

SI unit: Sievert (Sv) (still joules per kilogram because wR is unitless and dimensionless)

A useful tip: whenever the unit Sv is used we are estimating biological risk. Gray is strictly energy deposition without quatifying risk.

Weighting factors (ICRP):

- X-rays, gamma rays, beta particles: wR =1

- Neutrons: wR = 5–20.

- Alpha particles: wR = 20.

Key point: For diagnostic radiology, absorbed dose (Gy) and equivalent dose (Sv) are numerically the same, because wR = 1. But one estimates risk and the other doesn’t!

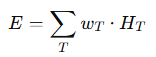

Effective dose (E)

Effective dose accounts for the fact that different organs and tissues have different sensitivities to radiation and ultimately tissue specific risk of stochastic effects.

Tissues are assigned a weighting factor based on their relative propensity to develop cancer after being exposed to radiation. These weighting factors are based on data from atomic bomb survivors and medical exposures. Each organ is assigned a weighting factor and all body organ weighting factors add up to 1. Therefore, the weighting factor adjusts for relative risk based on the organ exposed.

Effective dose is calculated by multiplying the equivalent dose by the tissue weighhting factor for each organ and adding the values together to get a total risk value.

This can be confusing, so let’s go through a quick example.

Suppose a patient undergoes a CT chest. From dosimetry data and modelling, the following absorbed doses (DT) to different organs are estimated:

| Tissue/Organ | Absorbed Dose DT (mGy) | Radiation weighting factor wR | Tissue weighting factor wT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs | 15 mGy | 1 (X-rays) | 0.12 |

| Breast | 10 mGy | 1 | 0.12 |

| Bone marrow | 5 mGy | 1 | 0.12 |

| Thyroid | 2 mGy | 1 | 0.04 |

| Skin | 3 mGy | 1 | 0.01 |

Step 1: Calculate equivalent dose for each tissue.

Because we are using X-rays the absorbed dose values = equivalent dose but now the unit is Sv. So this step is easy.

Step 2: Weight these equivalent dose values by tissue sensitivity = effective dose.

- Lungs: 0.12 × 15 = 1.8 mSv

- Breast: 0.12 × 10 = 1.2 mSv

- Bone marrow: 0.12 × 5 = 0.6 mSv

- Thyroid: 0.04 × 2 = 0.08 mSv

- Skin: 0.01× 3 = 0.03 mSv

Step 3: Add all the values up!

E = 1.8 + 1.2 + 0.6 + 0.08 + 0.03 = 3.71 mSv

So, the effective dose from this CT chest = ~3.7 mSv.

- This effective dose represents the average stochastic risk of this exam, distributed over all the patient’s tissues.

- For comparison:

- Chest X-ray ≈ 0.02 mSv.

- Natural background radiation per year ≈ 2–3 mSv.

- Thus, this CT chest ≈ equivalent to ~1–1.5 years of background exposure.

Important caveat: Effective dose is an estimate for a reference patient population, not the actual risk for an individual patient.

It’s a lot to cover I know 😅

Let’s take a moment to breathe. It’s been a long section. I really hope this has cleared up a few concepts for you. For those also studying CT and nuclear medicine, we will expand on these concepts in those courses looking at CTDI, radioactivity and more. Later in this module we will discuss dose area product (DAP) in flouroscopy.

But for now let’s leave it there. Revisit this section often to make sure these concept are clear.

Key takeaways

- Energy (eV, keV, MeV): fundamental unit for photons.

- Exposure (C/kg): ionisation in air.

- Absorbed dose (Gy): energy per mass of tissue.

- Equivalent dose (Sv): accounts for radiation type.

- Effective dose (Sv): accounts for tissue sensitivity.

Exam tips

- Exposure (C/kg) is only defined in air, not tissue.

- Absorbed dose vs equivalent dose vs effective dose → know the definitions and what each accounts for.

- Remember: Gy = energy absorbed, Sv = biological effect.

- For diagnostic radiography, Gy ≈ Sv because wR = 1.

- Absorbed dose is not measured directly in patients, but derived from exposure/air kerma.

- Ionisation chambers are the calibration standard.

Common exam mistakes:

- Confusing Gy vs Sv.

- Forgetting that effective dose uses tissue weighting.

- Over-interpreting effective dose as an individual risk (it is a population-based metric).

Are we finally done? Yes! Well at least for this first section.

Next, we’re going to review the X-ray machine. See you there!